- Entrevista a las creadoras en el Festival de Cine de Londres

Por Georgia Korossi

SemMéxico/BFI, Londres, 18 de octubre, 2024.- Ganadora del Gran Premio del Jurado de Cine Mundial en Sundance este año, Sujo es un poderoso drama de las directoras mexicanas Astrid Rondero y Fernanda Valadez sobre un niño de cuatro años cuyo padre, sicario de un cartel, es asesinado. Criado por su tía Nemesia en las afueras de una ciudad del centro de México acosada por los carteles locales, Sujo se expone tanto a la vastedad de la naturaleza como al espíritu nutricio de su tía, impregnado de un misticismo arraigado en la antigua cultura mexicana.

Más tarde, las circunstancias lo obligan a mudarse a la Ciudad de México, donde encuentra a otra mentora femenina en la universidad gratuita de la capital: la profesora de literatura Susan. En su determinación por ingresar a la universidad, su vida se convierte en un contraste impactante con la violencia que se desarrolla a su alrededor, hasta que su primo lo visita, intentando pedir dinero prestado para pagar al cartel. ¿Logrará Sujo escapar del ciclo vicioso de criminalidad que heredó de su padre?

Resaltando la cruda realidad de la guerra contra las drogas en México y los efectos devastadores que deja en la vida de los jóvenes, Sujo es la tercera colaboración cinematográfica de Rondero y Valadez. Es una película complementaria a su anterior trabajo sobre la migración, Sin señas partículares de 2020, que fue filmada en el estado de Guanajuato. Para filmar Sujo, Rondero y Valadez regresaron a la misma región, una parte del México rural que rápidamente se está convirtiendo en una de las zonas más peligrosas del país.

¿Por qué querían contar una historia sobre la guerra contra las drogas desde la perspectiva de un niño?

Astrid Rondero: Cuando estábamos investigando actores para nuestra película anterior (Sin señas particulares), fuimos a áreas rurales para hablar con la gente de allí. Al escuchar las historias de los jóvenes, muchos de ellos habían cruzado la frontera hacia Estados Unidos, por lo que tenían la experiencia de la migración. Los niños que se quedaron comenzaron a trabajar con los carteles locales de alguna manera, y parecía que no tenían muchas oportunidades. Así que, en ese momento, le dije a Fernanda que estos chicos que elegían la migración para mantenerse fuera de los carteles, o que se quedaban y se convertían en parte de eso, es una historia muy interesante. Y así nació la historia de Sujo.

¿Cómo fue trabajar con ellas y ellos?

Fernanda Valadez: Ese fue uno de los mayores desafíos. Cuando éramos más jóvenes y trabajábamos como asistentes de dirección, a Astrid generalmente la llamaban para comerciales o películas que incluían jóvenes. Así que ella tenía esa experiencia sobre las posibilidades y limitaciones de un niño de cuatro años. Dividimos nuestro trabajo, y Astrid estaba mayormente con los actores, en particular con los niños, ya que era increíble para construir un mundo imaginario que fuera seguro para que ellos trabajaran. Teníamos dos guiones para las escenas, uno para los niños y otro para los adultos. Lo que les decíamos fuera de cámara a los niños era diferente de lo que estaba escrito en el guion real.

¿Cómo garantizaron su seguridad en el set?

Rondero: Fernanda es originaria de Guanajuato, y la realidad es que esa área está cambiando rápidamente. Ya habíamos filmado allí antes, y la comunidad ya nos conocía, así que el elemento clave para nosotros fue encontrar una red de seguridad de personas a nuestro alrededor, junto con trabajar con las autoridades. Fuimos muy cuidadosas al movernos por áreas que ya conocíamos. Tuvimos un encuentro triste con un grupo armado, pero tuvimos mucha suerte de contar con el apoyo del gobierno, así que todo terminó bien.

¿Se identifican con la historia de Sujo a nivel personal?

Valadez: No tenemos esa experiencia de tanta adversidad, y eso es algo que sabíamos que teníamos que aceptar y usar como un dispositivo narrativo en la última parte de nuestra película. Me identifico por ser de esa región, por conocer a algunos de los niños y mujeres de la comunidad, y por ver cómo este pequeño pueblo se ha vaciado debido a la migración o al desplazamiento. Para nosotros, como una generación mexicana que se convirtieron en adulta cuando la crisis de violencia comenzó hace 20 años, es darnos cuenta de que muchos niños que nacieron en esta crisis ahora se están convirtiendo en adultos. Entonces, es una cuestión de cómo el mundo se abre o se cierra para un niño nacido en este contexto.

Rondero: Lo otro que tratamos de incorporar en la historia son las dificultades para lidiar con tu herencia, algo con lo que me identifico especialmente debido a una figura paterna difícil [en mi familia]. Ahora mi padre ya no está, pero me identifico mucho con el personaje en ese contexto. Además, solíamos ser docentes, por lo que, para nosotros, el significado y el alcance de lo que puedes hacer por un o una joven es importante. Por eso nos relacionamos tan fuertemente con la última parte de la historia en la Ciudad de México.

¿Pueden hablarnos sobre la paleta de la película y su colaboración con la directora de fotografía Ximena Amann?

Rondero: Conozco a Ximena desde la escuela; hemos estado trabajando juntas por mucho tiempo. El único momento en que dejamos de trabajar juntas fue con la película anterior, Sin señas particulares. Así que para nosotras es casi instintivo comunicarnos. Trabajamos en un storyboard una semana antes de filmar, y eso realmente ayudó. Por ejemplo, teníamos un calendario lunar para filmar con luna llena. No queríamos iluminar con luces eléctricas, solo queríamos electricidad básica para ciertas cosas. Creo que, para Ximena, la experiencia más interesante fue algo que Fernanda y yo aprendimos en nuestra película anterior: encontrar un equilibrio y trabajar con el menor equipo posible, pero con el mayor tiempo disponible, para tener suficiente margen para tener un mal día y luego volver a reunir las escenas.

¿Qué tan importante fue incluir a personajes femeninos fuertes, la tía de Sujo, Nemesia, y su maestra Susan?

Valadez: Creo que así ha sido en México: la resistencia a la violencia en las comunidades está siendo liderada por mujeres, las madres y hermanas de personas desaparecidas. Se convirtieron en activistas al buscar a sus seres queridos y darse cuenta de que no solo están buscando a sus hijos o hermanos, sino a todos los hijos y hermanos. Su participación activa en la resistencia contra la violencia se ha convertido en un gran movimiento en México, y queríamos honrar eso. De la misma manera, tratamos de expresar que la educación que Sujo recibe no es solo intelectual. Por supuesto que es importante ir a la universidad, pero es aún más importante que la educación espiritual y emocional que recibe de su tía le permita ser una persona amorosa y abierta al mundo.

¿Por qué eligieron un entorno rural para la infancia de Sujo?

Rondero: Una de las cosas que encendió nuestra imaginación fue el área en la que se ambientó la película. Es una zona antigua con muchos vestigios de culturas anteriores. Hay mucha energía [allí]. Queríamos que el personaje de la tía Nemesia estuviera arraigado a la tierra. Ella es como la líder espiritual de Sujo, su cuidadora, quien le enseñará valores morales, su conexión con la tierra y el misticismo del mundo. Eso es algo que también exploramos en nuestra película anterior, que tenemos esta terrible violencia en México, y a veces es difícil ver que esto sucede en lugares tan hermosos.

Valadez: Y como la historia de la infancia de Sujo se cuenta de manera episódica y abierta a todos los misterios del universo, no queríamos expresarlo de manera descriptiva. Queríamos usar una forma metafórica que esté relacionada con el espíritu de su tía. Sentir que hay cosas más reales de lo que pensamos, más concretas que nuestra vida material diaria.

Traducción: Sebastián Pizá Ruiz

Versión en Inglés

How we made our drug-war drama Sujo: “Many kids born into this crisis are now becoming adults”

Identifying Features filmmakers Astrid Rondero and Fernanda Valadez tell us about their latest drama Sujo, which follows a boy seeking to escape cycles of violence in rural Mexico.

SemMéxico/BFI, London, 18 of october, 2024.-Winner of the Grand Jury Prize for World Cinema at Sundance this year, Sujo is Mexican directors Astrid Rondero and Fernanda Valadez’s forceful drama about a four-year-old boy whose cartel gunman father is murdered. Raised by his Aunt Nemesia in the outskirts of a city in central Mexico that’s plagued by the local cartels, Sujo is exposed both to the vastness of nature and to his aunt’s nurturing spirit, which is infused with a mysticism rooted in Mexico’s ancient culture.

Later, circumstances force him to move to Mexico City, where he encounters another female mentor at the capital’s free university: literature teacher Susan. In his resulting determination to enter university, his life becomes a striking contrast to the violence unfolding around him – until his cousin visits, attempting to borrow money to pay the cartel. Will Sujo escape the vicious cycle of criminality that he inherited from his father?

Highlighting the stark reality of Mexico’s drug war, and the scarring effects that it leaves on the lives of young people, Sujo is the third feature collaboration by Rondero and Valadez. It’s a companion film to their earlier film about migration, 2020’s Identifying Features, which was filmed in the state of Guanajuato. To film Sujo, Rondero and Valadez went back to the same region, a part of rural Mexico that’s rapidly becoming one of the country’s most dangerous regions.

Why did you want to tell a story about the drug war from a child’s perspective?

Astrid Rondero: When we were researching actors for our previous film [Identifying Features], we went to rural areas to talk to the people there. From hearing the stories of young people, many of them had crossed the border to the US, so they had the experience of migration. The kids that stayed started working with the local cartels in some capacity, and it seemed like they didn’t have many chances. So, at that point I told Fernanda that these kids choosing migration to stay outside of the cartels – or staying and becoming part of that thing – is a very interesting story. And that’s how the story of Sujo was born.

What was it like working with them?

Fernanda Valadez: That was one of the greatest challenges. When we were younger and working as assistant directors, Astrid was usually called for commercials or films that included young people. So, she had that experience of the possibilities and limitations of a four-year-old. We divided our work, and Astrid was mostly with the actors, particularly with the kids as she was amazing in building an imaginary world that was safe for them to work in. We had two scripts for the scenes, one for the kids and one for the adults. What we said off-screen to the kids was different than what was written in the actual script.

How did you ensure their safety on set?

Rondero: Fernanda is originally from Guanajuato, and the reality is that area is changing quickly. We’d filmed there before, and the community already knew who we were, so the key element for us was finding a safety net of people around us alongside working with the authorities. We were very careful to move around areas that we already knew. We had a sad encounter with an armed group, but we were very lucky that we had the support of the government, so everything ended up being okay.

Do you relate to Sujo’s story on a personal level?

Valadez: We don’t have that experience of such adversity, and that’s something that we knew we had to accept and use it as a narrative device in the last part of our film. I relate by being from that region, of knowing some of the kids and women in the community and how this little town has become empty because of migration or displacement. For us, as a generation of Mexicans who became adults when the crisis of violence began 20 years ago, it’s realising that many kids who were born into this crisis are now becoming adults. So, it’s a question about how the world opens or closes to a kid born in this context.

Rondero: The other thing that we tried to enter in the story is the difficulties dealing with your inheritance, which is something that I especially can relate to because of a difficult father figure [in my family]. Now my father is no longer here, but I really relate with the character in that context. Also, we used to be teachers so, for us, the meaning and the scope of the things you can do for a young person is important. That’s why we relate so strongly with the last part of the story in Mexico City.

Can you tell us about the film’s palette and your collaboration with director of photography Ximena Amann?

Rondero: I know Ximena from school; we’ve been working together for a long time. The only moment that we stopped working together was with the previous film, Identifying Features. So, it’s second nature for us to communicate. We worked on a storyboard a week before shooting, and that really helped. For instance, we had a lunar schedule so we could shoot at full moon. We didn’t want to illuminate with electrical lights, we wanted just basic electricity for stuff. I think that for Ximena, the most interesting experience was something that Fernanda and I learned from our previous film: to have a balance and work with as little equipment as we can, with as much time as we can, to allow enough time to have a bad day and go back to get the scenes together.

How important was it to include these strong female characters, Sujo’s aunt, Nemesia, and his teacher Susan?

Valadez: I think that’s the way it’s been in Mexico: the resistance to violence in the communities is being led by women, the mothers and sisters of disappeared people. They became activists by looking for them and realising that they’re not just looking for their sons or brothers, but for all sons and brothers. Their active participation in the resistance against violence has become a big movement in Mexico, and we wanted to honour that. Likewise, we tried to express that the education Sujo receives is not only intellectual. Of course it’s important going to the university, but it’s even more important that the spiritual and emotional education he gets from his aunt allows him to be a loving person and open to the world.

Why did you choose a rural setting for Sujo’s childhood?

Rondero: One of the things that ignited our imagination was the area that the film was set. It’s an ancient area with a lot of vestiges of previous cultures. There’s a lot of energy [there]. We wanted to have the character of Aunt Nemesia rooted to the earth. She is like the spiritual leader of Sujo, his nurturer who will teach him morals, his connection with the earth and the mysticism of the world. That’s something that we also explored in our previous film, that we have this terrible violence in Mexico, and sometimes it’s difficult to see that this is happening in such beautiful places.

Valadez: And because the story of Sujo’s childhood is told in an episodic way and open to all the mysteries of the universe, we didn’t want to express that in a descriptive way. We wanted to use a metaphorical way that’s related to the spirit of his aunt. Feeling that there are more real things than what we think, more concrete than our daily material life.

SEM/BFI

https://www.cepal.org

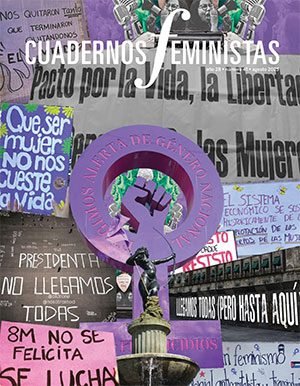

• Portada del sitio de la reunión:

https://www.cepal.org

• Portada del sitio de la reunión: